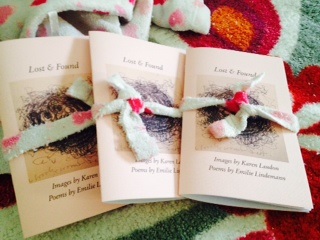

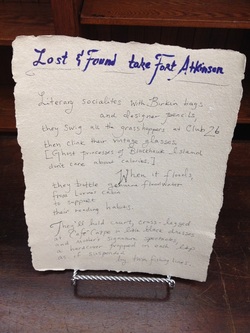

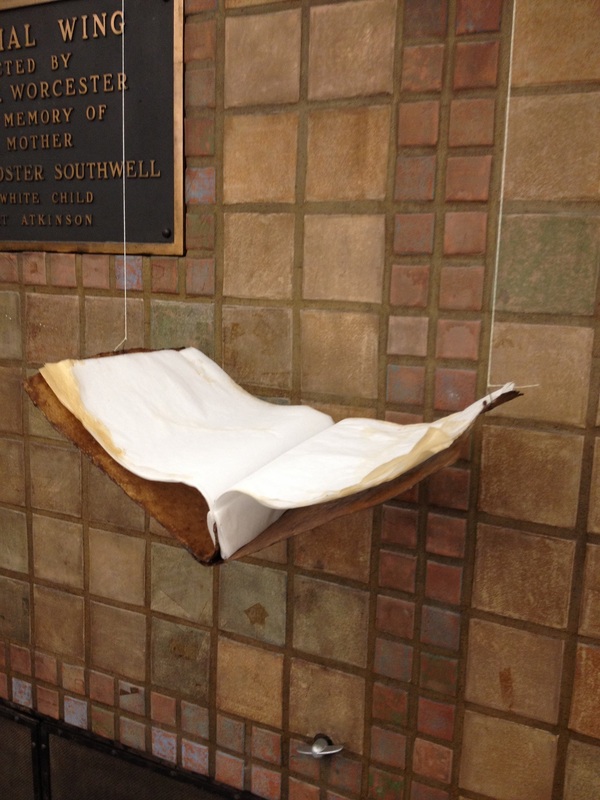

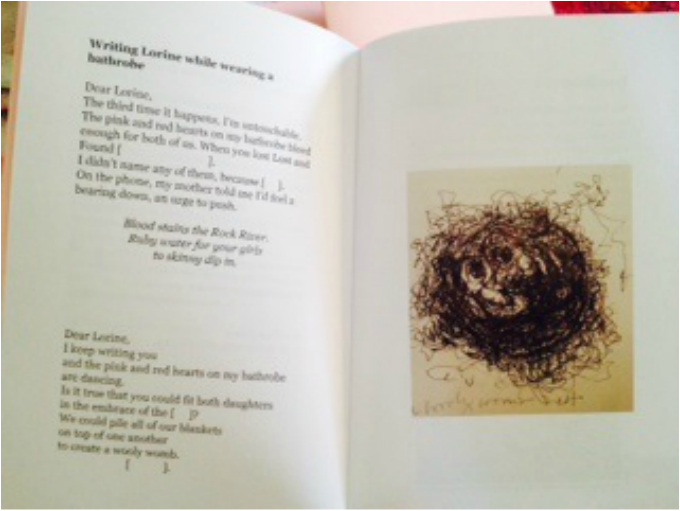

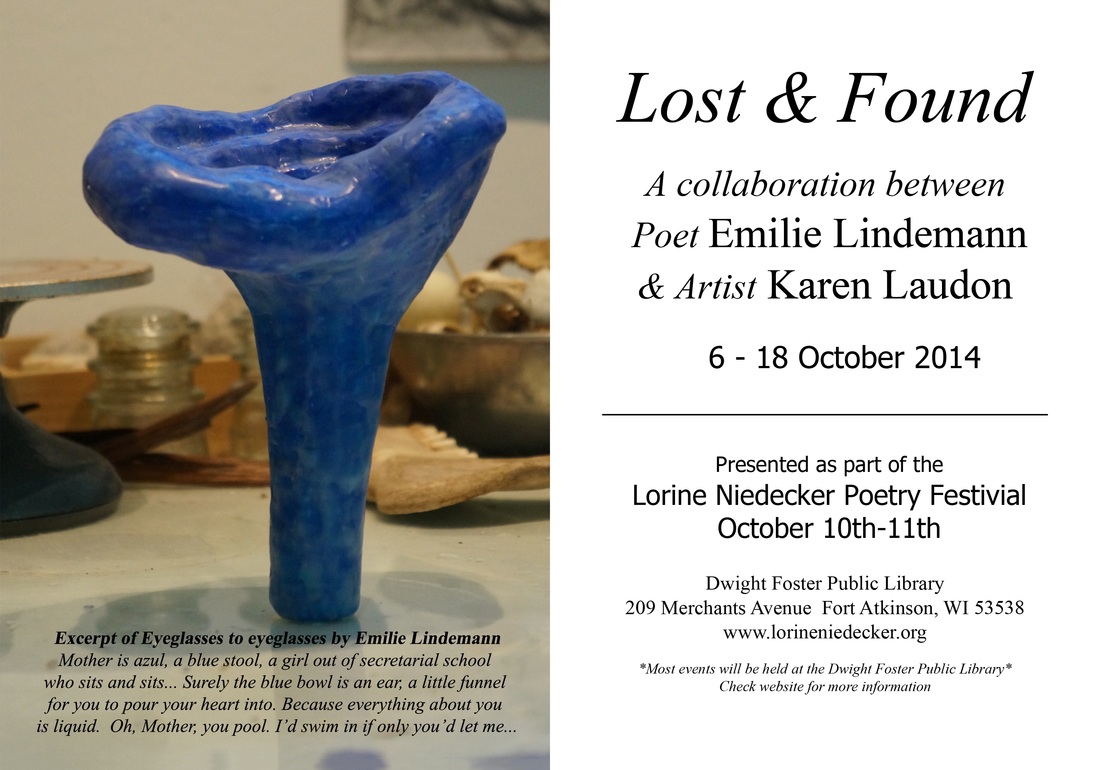

Photo: Erin LaBonte Photo: Erin LaBonte "Collaboration is a calling to work with and for others, in the service of something that transcends individual artistic ego and, as such, has to do with love, survival, generosity, and a conversation in which the terms of language are multidimensional." --Anne Waldman, "Going on Our Nerve: Collaborations Between Poets and Visual Artists" The lights are dim at the Brick Lot Pub in Sturgeon Bay. It's a Saturday night in early June and the place is packed for Steel Bridge Songfest. We're about to start our set. Although she considers herself more of a bassist than a drummer, Jena G. sits behind our ratty drum kit, brushes and sticks in hand. Bethany Lindemann, normally a vocalist and guitarist, has Jena's reddish-brown beauty of a bass. She's already in the zone, letting a few chords ring out. Though I'm not a singer, I awkwardly hold the microphone. "Let's get weird," I blurt. "Yeah," a few guys in a booth say, lifting their mugs of beer. When my sister Bethany suggested that I turn some poems from Small Adult Trees/Small Adulteries into songs for Villainess--our art rock side project, I was up for it. I was up for getting strange. I'm not a songwriter. Or a singer. At best, I'm a mediocre violinist. But I sang through three of the poems from my quirky tree people project, testing out melodies. Right away I realized how much condensing I would have to do to transform the poems into songs. My prose poems were wordy, too much of a mouthful for songs. I realized I'd have to add in some repetition. "Deciduous leaves, deciduous leaves, deciduous leaves on the small adult tree," I sang in the comfort of my living room. Bethany's driving bass part and vocal harmonies urged me on. Jena cautiously rattled the cymbals, then tapped intuitive, experimental rhythms on the floor tom. The result is a trio of shortish songs that we recorded in Bethany's basement. And then Stephen Spalding added in some eerie electric guitar and worked his magic with mixing. I don't think I have the musical vocabulary to describe how his mix affected the project, but let's just say the effects he applied to the tracks made the composition weirder, stranger, more Small Adult Trees-ish. Anne Waldman writes of collaboration and strangeness: "Something new, or 'other,' emerges from the combination that would not have come about with a solo act." And "something new or 'other'" did emerge when Bethany, Jena, and Stephen added their layers. Something strange and other emerged once again after visual artist Erin LaBonte responded with video. Erin had spent some time with the poem series. After she listened to the audio, she came back with a pocket-sized spiral notebook full of images and concepts scrawled in signature black Sharpie. Erin's experimental video asks viewers to enter a world of giant dandelion puffs, a curious new world where tree-people (or tree-dwellers?) are pregnant, are weaving streamers into branches. A world where leaves are plucked from trees and clenched palms open up to reveal ethereal blossoms. Rather than illustrate the songs, the experimental video responds to both the images and the music, creating a dream-like landscape. Collaboration allows for strength in numbers. How else could Bethany, Jena, and I have performed odd little tree songs in public? Collaboration also encourages the peculiar; it pushes us to move beyond our artistic comfort zones as we challenge one another to respond to images, phrases, melodies, and mixes. It encourages surprises. In "Going on Our Nerve," poet Anne Waldman writes, "The genre of collaboration is a social activity...You are not thinking about the concept, the finished product, or making money. So you surprise each other" (132). When collaborating, you have a built-in audience, so sometimes you create to flabbergast, to mystify, to delight your collaborator(s). We'll be sharing this collaboration during a poetry reading at LaDeDa Books & Beans in Manitowoc, WI on Thursday, Oct. 23 at 7 p.m. Or watch for the video on Vimeo or YouTube soon! Small Adult Trees/Small Adulteries (the poetry chapbook) is available through Dancing Girl Press. Work Cited Waldman, Anne. "Going on Our Nerve: Collaborations Between Poets and Visual Artists." Third Mind: Creative Writing through Visual Art. Ed. Tanya Foster & Kristin Prevallet. New York: Teachers & Writers Collaborative, 2002. Print. I have always been a fast eater, but let's just say that the morning of our presentation at the Wisconsin Poetry Festival I really chowed down in record time. I gulped a giant mug of coffee and scarfed down my incredibly hearty breakfast (think heaping platter of scrambled eggs, sausage, homemade toast + yogurt with granola). Because Karen Laudon lives in Madison and I live in rural Manitowoc, I had only experienced her sculptures for our collaborative installation Lost & Found (a series that explores Lorine Niedecker's missed motherhood and conflicted relationship with her mother) through snapshots via late-night text messages and batches of studies for sculptures sent in Sunday morning emails. So maybe (hopefully) it was understandable that I was edgy and anxious and giddy as I chugged my orange juice with breakfast and as Karen and I trotted the six blocks from our bed and breakfast to the Dwight Foster Public Library. We crunched through reddish-orange leaves past farmer's market stalls featuring honey taffy and gourmet marshmallows, and all I could think was, "We're late, we're late." When a well-meaning poetry-enthusiast wielding sidewalk chalk invited Karen and I to write our lives in six words on the sidewalk, I may have brushed past her with a curt "no thanks." We're late, we're late, I kept thinking. It was minutes before our 9 a.m. presentation for the Wisconsin Poetry Festival, and I would have to wait until after our session to finally see Karen's work in person. The other morning sessions following our presentation were so stimulating that I temporarily forgot my anxious quest to see the sculptures. C.X. Dillhunt of Hummingbird Magazine of the Short Poem gave an animated, meandering talk on the short poem--complete with a short poem literally unpacked from a plastic bag of thrift store finds. After a reading of "Pied Beauty" and a smattering of other short poems (Robert Creeley, Charles Simic, Cid Corman), C.X. revealed his "7 Recipes for a Short Poem." Among my favorite gems from his recipe file: Something thought short, said short, written short, read short: something the reader wants to reread and something the writer wants to perform again. Shoshauna Shy and the curators of HYBRID shared their experiences with bringing poetry into communities (think poetry and visual art in Madison taxicabs!). Then, poet Tom Montag, who recently released In This Place, unleashed "Ten Things I Know About the Short Poem" (#1= The frog must jump). And then it was time. Karen's Wooly Womb Nest sculpture in all its haunting, steel wool glory was one of the first pieces that caught my eye in the upstairs space adjacent to the Lorine Niedecker archives. The three-foot-diameter steel wool nest contains pockets of space that suggest embryos or perhaps sacs for Lost and Found, the [imaginary?] ghost daughters of Lorine Niedecker. Karen's bees' wax sculpture depicting Daisy Niedecker's head (complete with eyeglasses) sits atop a sturdy log. Brilliant cobalt blue ears suggest the hearing loss Lorine's mom suffered as well as the deep connection to water, to place. And then I saw them--twin books as light as air suspended from the gallery's fireplace mantel by fishing lines. Later a festival attendee would call the books bird-like, would see them in flight. But for now, all I could see was the negative space where the mischievous Lost and Found might have been moments before, aloof and knowing in little black dresses. A mystery woman in red glasses stepped closer and said what Karen and I might have been thinking: "Do you ever wonder if maybe the two of you are, like, spiritual descendants of Lorine Niedecker?" Maybe Lost and Found were looking on from afar, rolling their eyes.  Study for Twin Fishing Lines, K. Laudon (2014) Study for Twin Fishing Lines, K. Laudon (2014) Lost & Found take Fort Atkinson When Wisconsin poet Lorine Niedecker (1903-1970) became pregnant, lover and fellow poet Louis Zukofsky persuaded her to have an abortion. According to Jerry Reisman, Lorine named the twins ‘Lost’ and ‘Found' and "ached for her twins all the years of her life." Literary socialites with Birkin bags and designer pencils, they swig all the grasshoppers at Club 26 then clink their vintage glasses. [Ghost princesses of Black Hawk Island don’t care about calories.] When it floods, they bottle Genuine floodwater from Lorine’s cabin to support their reading habits. They’ll hold court, cross-legged at Café Carpe in little black dresses and mother’s signature spectacles, a hardcover propped on each lap as if suspended by twin fishing lines. --poem first published in Verse Wisconsin Note: Lost & Found is on display at the Dwight Foster Public Library in Fort Atkinson, WI through October 18.  I spent Monday evening sitting on my living room floor, cutting an old pink-heart-flecked bathrobe into narrow strips. It felt destructive--but only at first. I cut and cut and cut and bits of terrycloth confettied my floral area rug. * Maybe it was a sort of poetry nesting that compelled me to cut my bathrobe into shreds. In three days, Madison-based visual artist Karen Laudon and I will be presenting Lost & Found, our collaborative installation of poetry, sculpture, and paintings, at the Lorine Niedecker Wisconsin Poetry Festival in Fort Atkinson, WI. The bathrobe strips became ties for a D.I.Y. chapbook of my poems and Karen's studies for her sculptures. * In 1935, Wisconsin poet Lorine Niedecker became pregnant after an extended visit to her lover and mentor Louis Zukofsky in New York. The story goes that she wanted to keep the baby and raise it on Blackhawk Island in Wisconsin. Zukofsky insisted she have an abortion, and it was discovered that Niedecker had been carrying twins. According to Jerry Reisman, a friend of the couple, Niedecker "ruefully named them 'Lost' and 'Found.'" Reisman claims that "Physically, [Niedecker] recovered quickly; but I think she must have ached for her twins all the years of her life" (qtd in Peters 49). Lost & Found explores Niedecker's missed motherhood, her conflicted relationship with her mother Daisy, and thoughts on loss and unrealized potential. * Did Lorine Niedecker wear a bathrobe? I'm not sure. The pink heart bathrobe that we used for the Lost & Found chapbook was with me through three miscarriages. After the third time, it sat washed and clean in a laundry basket for months. For Christmas 2013 my husband surprised me with a new bathrobe--plush pink and dotted with owls. Did I wear it while writing poems that imagine Lost & Found as mischievous 27-year-old ghost daughters, as invisible literary socialites of Blackhawk Island? Maybe I was wearing it when I received photos of Karen's new studies for sculptures. Maybe I wore the fresh-start owl bathrobe while I wrote poems that responded to Karen's artwork. By the time I had written all of the poems for Lost & Found, I found out my husband and I were expecting our first child. Baby S. is kicking (in utero) as I type this. Lost & Found (the installation) is on display at the Dwight Foster Library in Fort Atkinson until October 16. Karen and I will discuss our collaborative process during the 9 a.m. Wisconsin Poetry Festival session on Saturday, October 11.

Work Cited Peters, Margot. Lorine Niedecker: a Poet's Life. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2011. Print. |

Emilie Lindemann is the author of mother-mailbox (forthcoming from Misty Publications) and several poetry chapbooks, including Small Adult Trees/Small Adulteries and Queen of the Milky Way (both from dancing girl press). Archives

August 2021

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed